Giving a charity a strong story and a clear sense of direction

1625 Independent People

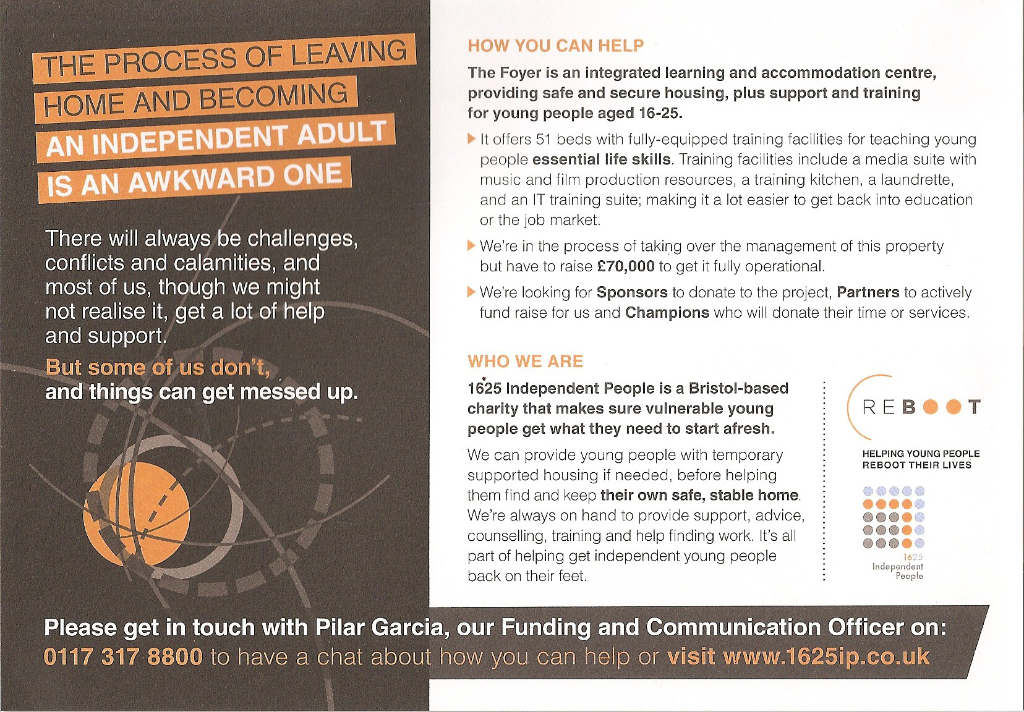

1625 Independent People is a Bristol-based charity that makes sure vulnerable young people get the support they need to make a fresh start with their lives. Amongst other things it provides young people with temporary supported housing before helping them find and keep their own safe and stable home. Alongside this they offer whatever else is needed in the way of support, advice, counselling, training and help with finding work – everything to help them get back on their feet and self-sufficient.

The charity wanted help with an urgent campaign – they needed to raise £70,000 in just three months to get an integrated learning and accommodation centre fully operational. Pilar Garcia, the charity’s Funding and Communications Officer, along with marketing consultant Ryan James, asked myself and designer Lizzie Everard to help them create a story that would sell the idea – a concept that could be used on flyers, web pages and other marcoms to attract sponsors, donors and partners.

Growing pains

As Pilar and Ryan outlined the task I realised just how challenging it really was. For starters the charity was a recently completed amalgamation of two separate organisations. The new entity was still taking shape so the culture, values, mission and sense of purpose were all embryonic. But that was the least of the problems.

Two tribes

The stakeholders were very diverse. On the one hand you had those who could provide financial support. These included local councils, The National Lottery, corporate sponsors and private individuals. They needed convincing that this was a worthy and well run organisation that genuinely achieved worthwhile results. They were accountable to taxpayers, trustees, directors, shareholders and their individual consciences. What they were looking for (although they might not express it quite so bluntly) was a return on investment.

On the other were the vulnerable young people themselves. This group could not be more different from the first. For starters there was the generation gap between the two. Then there was the fact that the young people had been let down by adults and those in authority – they found it hard to trust anyone from either of those groups. They therefore needed convincing that the charity was “on their side” and had a genuine understanding of their situation, challenges and needs – otherwise they wouldn’t approach it and ask for help. What they were looking for was empathy and they were seeing things, not from a comfortable establishment perspective, but from the street.

This created a huge communication challenge – how do you come up with a message, look and feel that would somehow reconcile these differences and appeal to both audiences?

Judge not

There was a further problem. Many of those in a position to offer financial support were reluctant to do so because they harboured the feeling that many vulnerable young people were partly to blame for the mess they found themselves in.

To maximise the effectiveness of the fundraising efforts we had, somehow, to tackle this attitude. We had to present an alternative narrative. One that reminded potential funders that the transition from childhood to adulthood is a very difficult one and that everyone struggles with it. We needed to point out that most of us were lucky enough to be surrounded by people who helped us get through it. But that there are other instances where that essential help isn’t forthcoming. So rather than blaming the young person who goes off the rails we need to be thankful for our own luck – and help the ones who have been let down.

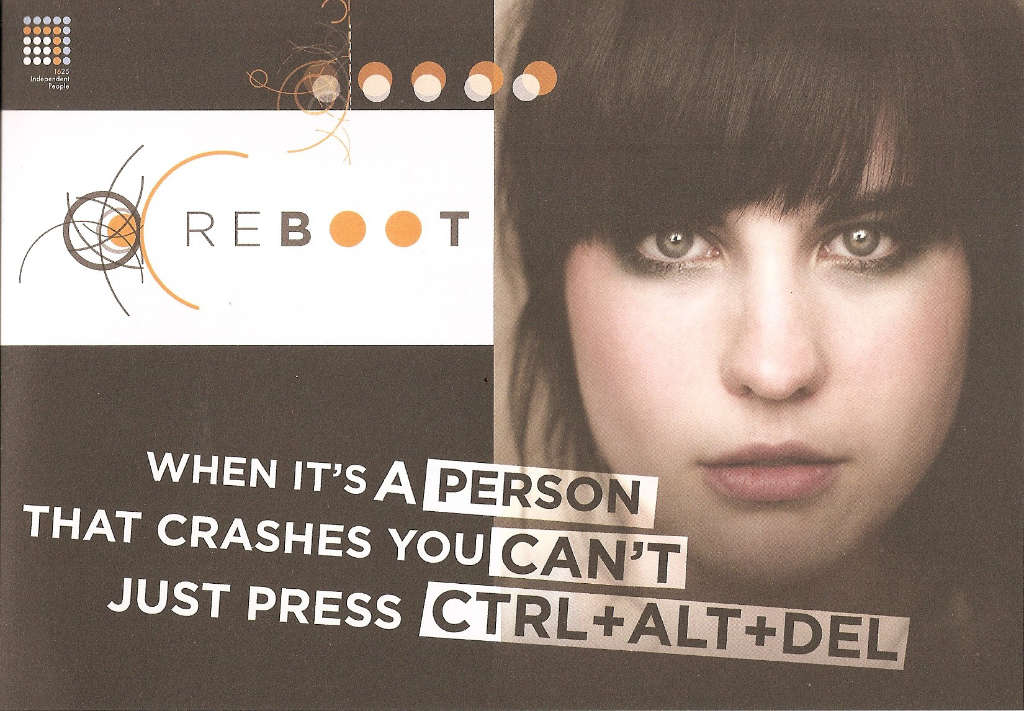

Download 65% complete

But how do we do that in a succinct and powerful way that’s going to grab attention? I came up with an analogy that I felt everyone would relate to. Adulthood is like a set of programs each of us has to download. And who hasn’t had trouble downloading new stuff onto their computer then getting it to integrate with all the other programs that are already there? When it happens we feel so helpless. But then we call a helpline, or ask a friend, and they change a few settings then reboot – and bingo, it works!

I felt this was a good way to make potential funders and donors think twice before blaming the young person for what has gone wrong. And to make those adults realise that people, like computers, need some help getting new programs to download – only it’s a lot harder, and takes much longer, when it’s a human being you are trying to reset and reboot.

This narrative had the benefit of giving pause for thought to those who might otherwise have been quick to blame, and therefore not give. It also sent a clear message to vulnerable young people that the team at the charity would not judge them but genuinely understood what they were going through. Finally, and perhaps most important of all, it gave those in the charity a positive and appealing message they could work with when dealing with those two very different groups of people. What’s more, it provided a clear sense of purpose and a mission they could believe in – it validated everything they were doing.